Lessons learnt after a humbling year of maths teaching.

A dramatic person may say that mathematics is the closest we will ever go to living out our dreams. Whatever the feelings towards the topic – there is intergenerational polarisation that comes from maths. Most people fall into a camp of love or hate.

What has been inspiring over the last decade since leaving high school myself, has been to see the shift in how the topic of mathematics is taught. The old ways of learning by rote from textbooks are no longer inherently a default strategy.

Entering 2020 I had one major obstacle to overcome in my mathematics pedagogy. How do I factor in a wildly inconsistent attendance? Most of my teacher training had built from the assumption that your student cohort will attend each day. Occasionally you may need to alter your planning to accommodate a student who is away for a few days. This obstacle was in place, before the factors mentioned at the beginning of the previous blog.

We know that attendance is not necessarily correlated with academic outcomes1. But if you never attend school – you will struggle to make progress on your learning2. In the first term or two I was still stuck in old habits and trying to teach my maths program like I would in a mainstream classroom. This changed the more I reflected on my teaching.

Halfway through the year I identified that I needed to target more content areas across a wider span of abilities. This would require maths rotations and additional planning. It was not easy, but I felt it was a necessary evil to keep targeting the relevant level my students were at.

It proved a bridge too far and by the end of term 3 it felt as though our maths was no longer moving forward. I decided to throw the baby out with the bathwater for term 4. Our mathematics time and space became unstructured and reliant on a menu approach.3

I was astounded at the results. A classroom of teenagers would enter after a recess break and settle into half a dozen different mathematical activities. No prompting (mostly) before they would settle into a task. As an educator I was then able to target the menu activities around the mathematical progression we needed to focus on – for example, additive and multiplicative thinking.

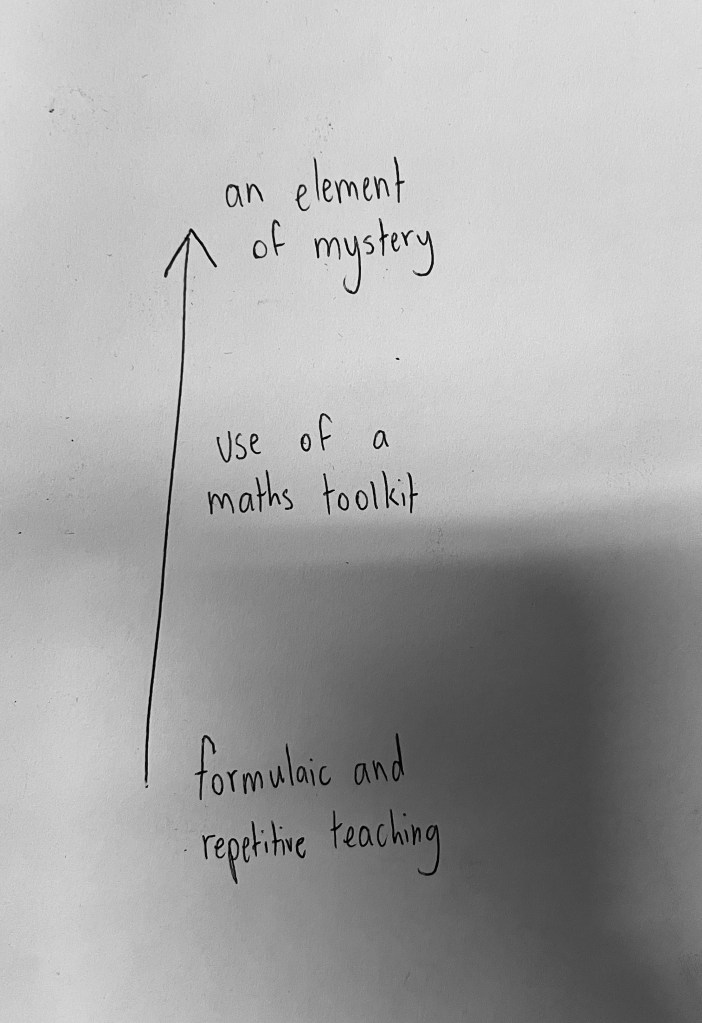

The approach was not perfect – as with all teaching pedagogies. At times students would be willing to complete an initial activity before losing interest in completing any additional tasks. But I feel it lifted our standards in class from a formulaic repetition of operation-focused problems, into students using their mathematical toolkit. Each activity required the identification of what skills would be required for completions.

A focus for next year’s planning will be to lift this again. To use the foundation of a maths menu, but to also introduce week long micro-units that have an element of mystery involved. These units intend to draw our critical thinking and creativity from the class.

After all, while it is nice if we have numerate students who can engage in the mathematical literacy of the world – what if we facilitated students with the fundamental skills to adapt to a future world that we can’t predict.

—

References

1Guenther, J. (2013). Are we making education count in remote Australian communities or just counting education?. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 42(2), 157-170.

2Purdie, N., & Buckley, S. (2010). School attendance and retention of Indigenous Australian students.

3Reinken, C. (2020). How to Use Choice Boards to Differentiate Learning – The Art of Education University. Retrieved 15 December 2020, from https://theartofeducation.edu/2012/07/11/how-to-use-choice-boards-to-differentiate-learning/

AITSL Standards: