Photo by Kirill Tonkikh on Unsplash

Case Study: Year 10 Physics

Rationale (500 words)

Project-based Learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that offers a powerful framework for teaching integrated science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) in classrooms. By engaging students in authentic, real-world projects, PBL promotes deeper learning, fosters critical thinking and problem solving skills, and facilitates the integration of STEM disciplines (Forbes et al., 2021). This rationale will explore the benefits and evidence that supports the adoption of PBL for teaching integrated STEM, drawing on relevant research from the literature.

Firstly, PBL promotes deeper learning by contextualising STEM concepts within real-world problems and projects. It is important to pose a realistic situation at the beginning of a unit and using the need to create a deliverable product, in order to drive the course content (Lee & Galindo, 2021). There is a need to encourage students to actively construct knowledge by investigating and solving complex problems. PBL has been found to motivate students and to foster a higher level of engagement compared to traditional learning settings (Bell, 2010). By engaging in hands-on activities and inquiry-based learning, students develop a deeper understanding of STEM concepts.

PBL cultivates critical thinking and problem-solving skills, which are essential for success in STEM fields. Students can build from the essential background understanding of each STEM discipline and apply this knowledge more broadly using a range of thinking approaches (Forbes et al., 2021). PBL provides opportunities for students to tackle open-ended problems, work collaboratively and to employ the higher-order thinking skills. This is reinforced by an ACARA report (2016) that reaffirmed how learning areas working together can further support a students’ retention of STEM knowledge (Forbes et al., 2021). By designing and creating solutions to real-world problems, students develop resilience, creativity, and adaptability (Neber et al., 2012). By developing a holistic understand of STEM it fosters the ability to then make the connections across the different disciplines in the STEM field. This integration mirrors the interdisciplinary nature of real-world STEM challenges and prepares students for the dynamic nature of modern careers (Nurtanto et al., 2020).

It can also be said the PBL aligns with current educational reforms that emphasise student centred, active learning approaches. Research from abroad shows education systems looking to prepare students for the continuously changing world and to equip them with skills needed to investigate, process data, work in teams, offer solutions to non-standard situations, and to analyse and set goals for future tasks (Birzina et al., 2021). PBL strategies are also being adopted in higher education settings as further evidence of the success of the approach (Lock & Koh, 2020).

To summarise , Project-based Learning (PBL) is an effective approach for teaching integrated STEM. Through authentic projects, PBL promotes deep learning, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills while integrating STEM disciplines. Students engage in hands-on activities, fostering a profound understanding of STEM concepts and developing essential skills like collaboration, resilience, creativity and adaptability. Aligned with student-centred and active learning approaches, PBL supports educational reforms. By adopting PBL educators create engaging experiences empowering students to thrive in STEM and navigate future challenges.

References:

ACARA (Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority) (2016). STEM Connections project report. Retrieved from http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/media/3220/stem-connections-report.pdf

Bell, S. (2010). Project-based learning for the 21st century: Skills for the future. The clearing house, 83(2), 39-43.

Birzina, R., Pigozne, T., & Lapina, S. (2021). Trends in STEM teaching and learning within the context of national education reform. In The Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference Rural Environment. Education. Personality (REEP) (pp. 41-49).

Forbes, A., Chandra, V., Pfeiffer, L., & Sheffield, R. (2021). STEM education in the primary school: a teacher’s toolkit. Cambridge University Press. https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9781108811989

Lee, J. S., & Galindo, E. (2021). Examining Project-Based Learning Successes and Challenges of Mathematics Preservice Teachers in a Teacher Residency Program: Learning by Doing. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 15(1).

Lock, J., & Koh, K. (2020). Instructors’ Professional Learning and Implementation of Problem-Based Learning in Higher Education. In Handbook of Research on Innovative Pedagogies and Best Practices in Teacher Education (pp. 69-84). IGI Global.

Neber, Heinz, and Birgit J. Neuhaus. “Creativity and problem-based learning (PBL): A neglected relation.” Creativity, talent and excellence. Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2012. 43-56.

Nurtanto, M., Fawaid, M., & Sofyan, H. (2020, July). Problem based learning (PBL) in Industry 4.0: Improving learning quality through character-based literacy learning and life career skill (LL-LCS). In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1573, No. 1, p. 012006). IOP Publishing.

Project Identification (150 words)

The proposed real-world project for Year 10 science students is titled “Designing an Autonomous Vehicle” and focusses on the application of Newton’s Laws of Motion. This project is designed to provide students with a hands-on experience that integrates STEM disciplines and promotes a deeper understanding of physics concepts.

This project is appropriate in our context as it aligns with the Year 10 science curriculum and allows for the tactile strength of our student cohort. By engaging the students in the project, it allows them to explore and apply the principles of motion, forces and energy.

Implementation of the project will involve students working in teams to design and build a prototype of an autonomous vehicle that demonstrates Newton’s Laws. The will be required to consider factors such as velocity, acceleration, and friction in their design. Students will conduct experiments, collect data, and analyse the performance of their vehicle to ensure it operates in accordance with the laws of motion.

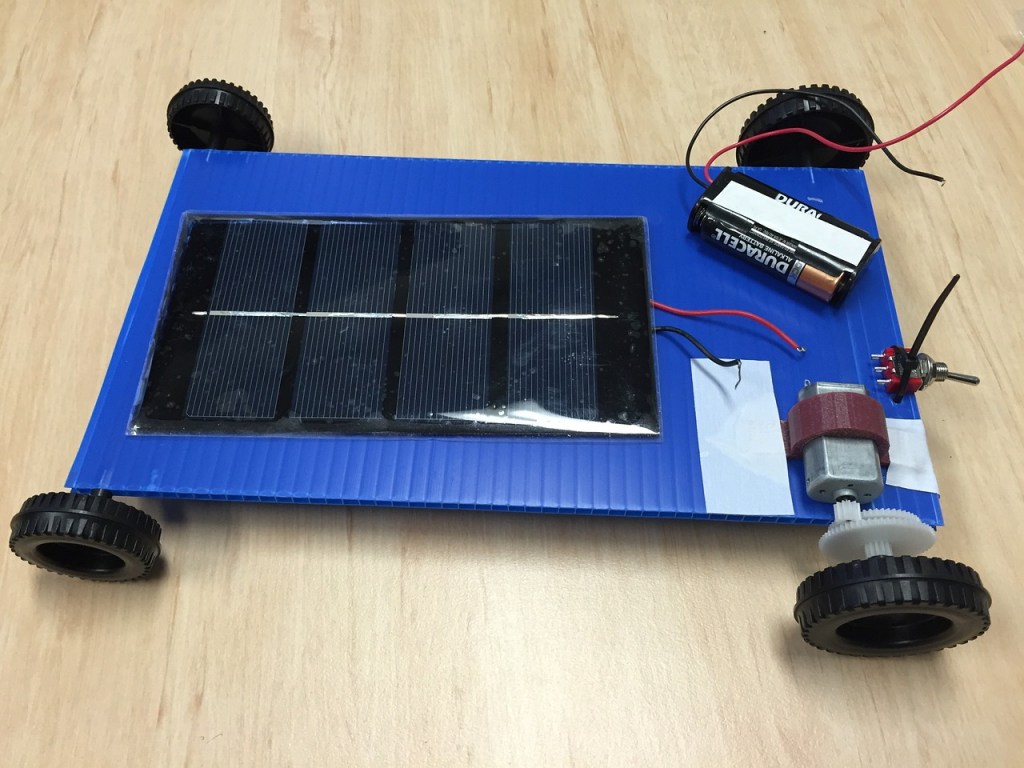

Here is an example of the prototype the project aims to deliver:

Image available through Creative Commons licence and Pixabay

The project will provide students with opportunities to develop their critical thinking, problem-solving, and collaboration skills as they work together to overcome design challenges and optimise the performance of their vehicle.

Curriculum Connections (50 words)

This project connects in with Australian Curriculum content descriptor AC9S10U05: “investigate Newton’s laws of motion and quantitatively analyse the relationship between force, mass and acceleration of objects” (ACARA, 2023). Students will also draw from the science inquiry strand of the Australian Curriculum with AC9S10I02: “plan and conduct valid, reproducible investigations to answer questions and test hypothesis, including identifying and controlling for possible sources of error and, as appropriate, developing and following risk-assessments” (ACARA, 2023).

Assessment ideas (50 words)

This project can be run to meet Australian Curriculum performance standards while still allowing students the chance to explore earning credits through the South Australian Certificate of Education (SACE). As such – this project will be evaluated as a summative activity.

The project can be assessed against students’ design process, prototype functionality, data collection and analysis as well as their ability to apply Newton’s Laws of Motion. Students can give project presentations, prototype demonstrations, written reflections and participate in group discussions.

I will create a rubric for students to review so they understand the specific criteria related to the project objects and desired learning outcomes.

Teaching and learning processes (1250 words)

The teaching and learning process will follow a cyclical approach as outlined by Forbes et al. (2021). As such, this process has been broken into 5 phases: Ask, Imagine, Plan, Create and Improve as well as a reflection component at the end.

Phase 1: Ask – How will the students define and understand the project requirements?

For this project there will be an emphasis on the importance of documenting the learning journey: explaining to students that they will be recording their progress and reflections throughout the project. I will encourage them to keep a digital portfolio where they can document their work samples, images, videos, and written reflections, which has been shown to have a benefit in retention of knowledge (Moust et al., 2021). This documentation will include both successful designs and investigations that did not work out as intended. There will be a focus on providing guidance on selecting and organising evidence. It is essential to help students understand what constitutes a relevant work sample and evidence to demonstrate their evidence. This empowers students to strengthen their self-determination which can lead to positive outcomes for their education journey (Tirado-Morueta et al., 2021). As part of this first phase it is important to set clear expectations at the beginning for students. There is a need for ongoing documentation and the collection of evidence from the start of the process (Forbes et al., 2021).

Phase 2: Imagine – How will the students investigate and research about the project?

Students will engage in different research tasks to individual that are on an individual level, or in groups, to explore the principles of Newton’s Laws of Motion. It will also be important for students to explore how Newton’s laws can be applied in autonomous vehicles. Students will be encouraged to gather information from reliable sources such as scientific journals, books, and reputable websites. Phase 2 needs to empower students to ask questions to allow the research for their projects to be comprehensive and strengthen their project (Forbes et al., 2021). As part of the teaching process it is important to provide opportunities for students to collaborate and share their research findings through presentations, group discussions, or online forums. It will be important to guide students in critically analysing the research and identifying key concepts and principles relevant to their project.

Phase 3: Plan – How will the students design and plan their preferred solution.

As part of the teaching process it will be important to facilitate brainstorming sessions to generate ideas for the design of the autonomous vehicle prototype. It will be important to encourage students to consider factors such as velocity, acceleration, and friction in their design process. There will be the provision of design tools an software that students need in order to enable them to create sketches, diagrams, or 3D models of their proposed solution. This supports the need that in PBL students have to go beyond knowledge and to a deeper level of learning where understanding is applied (Miller & Krajcik, 2019). It will be important for students to create a detailed plan, including a SMARTGOAL, that outlines the materials, timeframes, and milestones for the project. Students will need to consider the feasibility of their design and the resources required for implementation (Forbes et al., 2021). They will need to check on the availability of materials and if there is a cost associated. They also should consider any logistical challenges that may arise during construction of the prototype.

Phase 4: Create – How will the students produce the preferred solution?

It is important once students have worked through phase 3 and planned a realistic process that they are provided access to materials and resources required for building the autonomous vehicle prototype (Forbes et al., 2021). As part of the teaching process students will be facilitated with hands-on activities. This will allow students to construct their prototypes, ensuring safety precautions are followed. While creating, students will be encouraged to document their progress. There will be an emphasis, as part of the learning process, for a collaborative environment to take place through the PBL. Students should seek feedback from peers and make iterative improvements to their prototypes (Hendarwati et al., 2021). This allows the opportunities to benefit from diverse perspectives, receive constructive criticism, and to collaborate on problem-solving challenges.

Phase 5: Improve – How will the students evaluate their preferred solution?

During the improvement phase, students will engage in a systematic evaluation of their preferred solution, which involves conducting tests and experiments to assess the performance of their autonomous vehicle prototypes. To ensure effective evaluation, students will receive explicit teaching on data collection methods and techniques for analysing the results obtained from their tests (Forbes et al., 2021). This instruction will enable students to critically examine how well their prototypes align with the principles of Newton’s Laws of Motion, a fundamental aspect of their project. As part of the teaching process, facilitating discussions is essential to encourage students to reflect on the strengths and weaknesses of their designs. Through these discussions, students can identify areas for improvement and propose modifications that would enhance the performance and functionality of their autonomous vehicles. The reflective component of this phase helps students deepen their understanding of the design process, learn from their mistakes, and develop a growth mindset (Widarni, 2023). By actively engaging in this reflective practice, students gain insights into their own learning journey and become more capable of taking ownership of their project outcomes. The peer feedback process established in Phase 4 also plays a crucial role in the improvement stage. Students will have the opportunity to provide feedback to their peers on their prototypes, highlighting areas of strength and suggesting potential improvements. This collaborative feedback exchange fosters a supportive learning community where students learn from one another, gain different perspectives, and refine their designs based on constructive criticism (Hendarwati et al., 2021). By integrating systematic evaluation, reflective discussions, and peer feedback into the improvement phase, teachers can guide students towards a deeper understanding of their prototypes’ performance and the design process as a whole. This phase not only reinforces the principles of project-based learning but also empowers students to actively participate in the refinement of their solutions, ultimately leading to a more meaningful and impactful learning experience.

Opportunities for teacher improvement

Teachers are encouraged to reflect on the outcomes of this PBL teaching framework. It is important to make sure that the final assessment method used aligns with the desired learning outcomes.

Techers can reflect on the level of differentiation provided in this project which is known to have a positive impact on student outcomes (Bender, 2012). Throughout the PBL process students were encouraged to reflect on their process and teachers should could take this moment to think back on whether this was achieved successfully. It is important to make sure that through the PBL approach there was a clear integration of STEM disciplines. A major theme to reflect on, is as a facilitator of the project was the project effectively guided and support so that students could achieve success.

References:

Bender, W. N. (2012). Project-based learning: Differentiating instruction for the 21st century. Corwin Press.

Bachri, B., & Sa’ida, N. (2021). Collaborative Problem based learning integrated with online learning. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning (iJET), 16(13), 29-39.

Forbes, A., Chandra, V., Pfeiffer, L., & Sheffield, R. (2021). STEM education in the primary school: a teacher’s toolkit. Cambridge University Press. https://bookshelf.vitalsource.com/books/9781108811989 Hendarwati, E., Nurlaela, L.,

Moust, J., Bouhuijs, P., & Schmidt, H. (2021). Introduction to problem-based learning.

Routledge. Miller, E. C., & Krajcik, J. S. (2019). Promoting deep learning through project-based learning: A design problem. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 1(1), 1-10.

Tirado-Morueta, R., Ceada-Garrido, Y., Barragán, A. J., Enrique, J. M., & Andujar, J. M. (2021). The association of self-determination with student engagement moderated by teacher scaffolding in a Project-Based Learning (PBL) case. Educational Studies, 1-22.

Widarni, W. (2023). Analyzing Students’ Self-Reflection on Project-Based Learning and Caption Text. Journal of English Education and Teaching, 7(1), 78-96.